The most common Scandinavian place name element in England is "by" (pronounced "bee"). "Bee" place names account for 1.6% of all place names. In Lincolnshire this increases to 20.4%, a figure which is extraordinarily high. Other Scandinavian place name elements found there include: "toft", "beck" and "thorpe". These are much less common, accounting for 1.1%, 0.8% and 0.5% respectively.

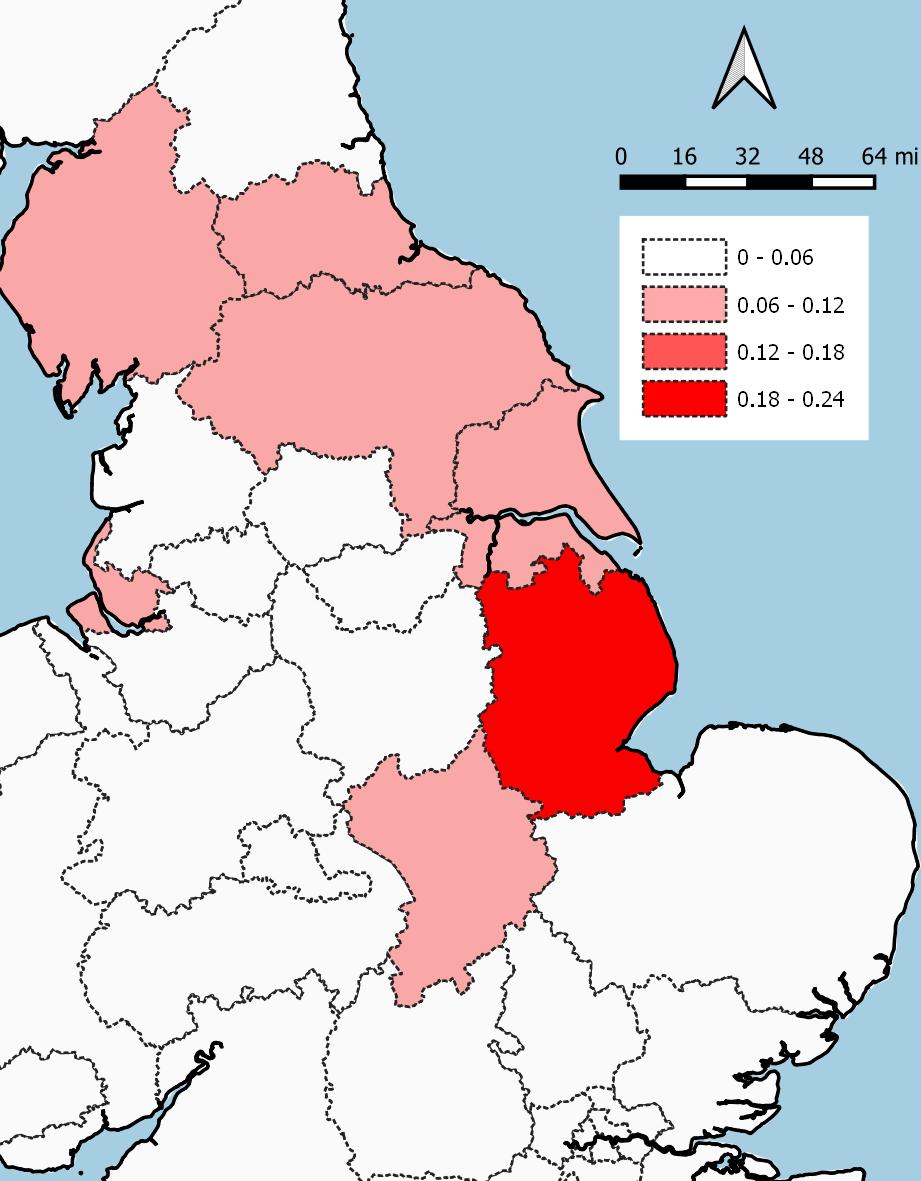

Figure 1 Proportional density of "bee" place names in England by Region

English "bee" place names are centred on Lincolnshire and fan out in an arc to the north-west and to the south-west. Local clusters also occur in some coastal areas of East Anglia and the North-West. Figure 1 plots the proportional density of "bee" place names by region. By using proportions we can make comparisons across geographies with different population structures.

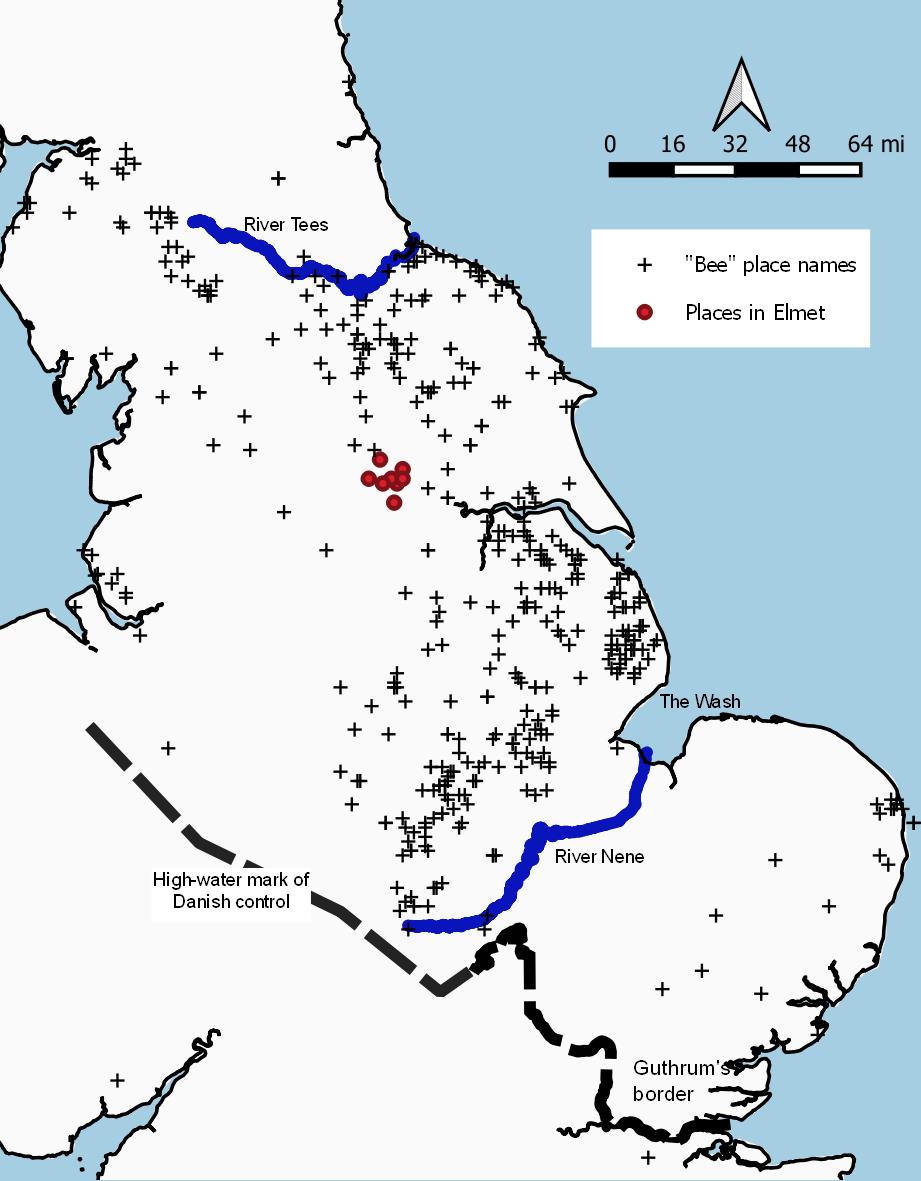

Figure 2 Individual “bee” place names in Scandinavian England.

Figure 2 plots individual "bee" place names. It also shows the southern limit of Scandinavian Viking age control (subsequently Scandinavian England) based on the southernmost fortifications established during the Saxon resurgence and the treaty between Alfred and Guthrum (Guthrum, undated). By plotting the individual place names we can see precisely how they are distributed across the land. They are usually attributed to Viking age settlement, so we might expect to find them everywhere throughout Scandinavian England. However this is not the case. They stop quite abruptly at the Wash (that divided the pre-Viking age kingdoms of Lindsey and East Anglia) and at the River Tees (that divided the pre-Viking age kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira). They peter out gradually in West Yorkshire and are absent from the area surrounding towns in the former Celtic kingdom of Elmet (Elmet, 2021).It is a mystery why "bee" place names should be so common in some parts of Scandinavian England and completely absent in others. Why is it that we can step across the River Tees and find almost no "bee" names on its northern banks? Why can we cross the Wash from southern Lincolnshire into the north of Norfolk to an area almost devoid of them? Why are they so plentiful in Yorkshire, yet so scarce across the Pennines in Lancashire? I considered these anomalies in another essay which focussed on England. I turn now to the international context.

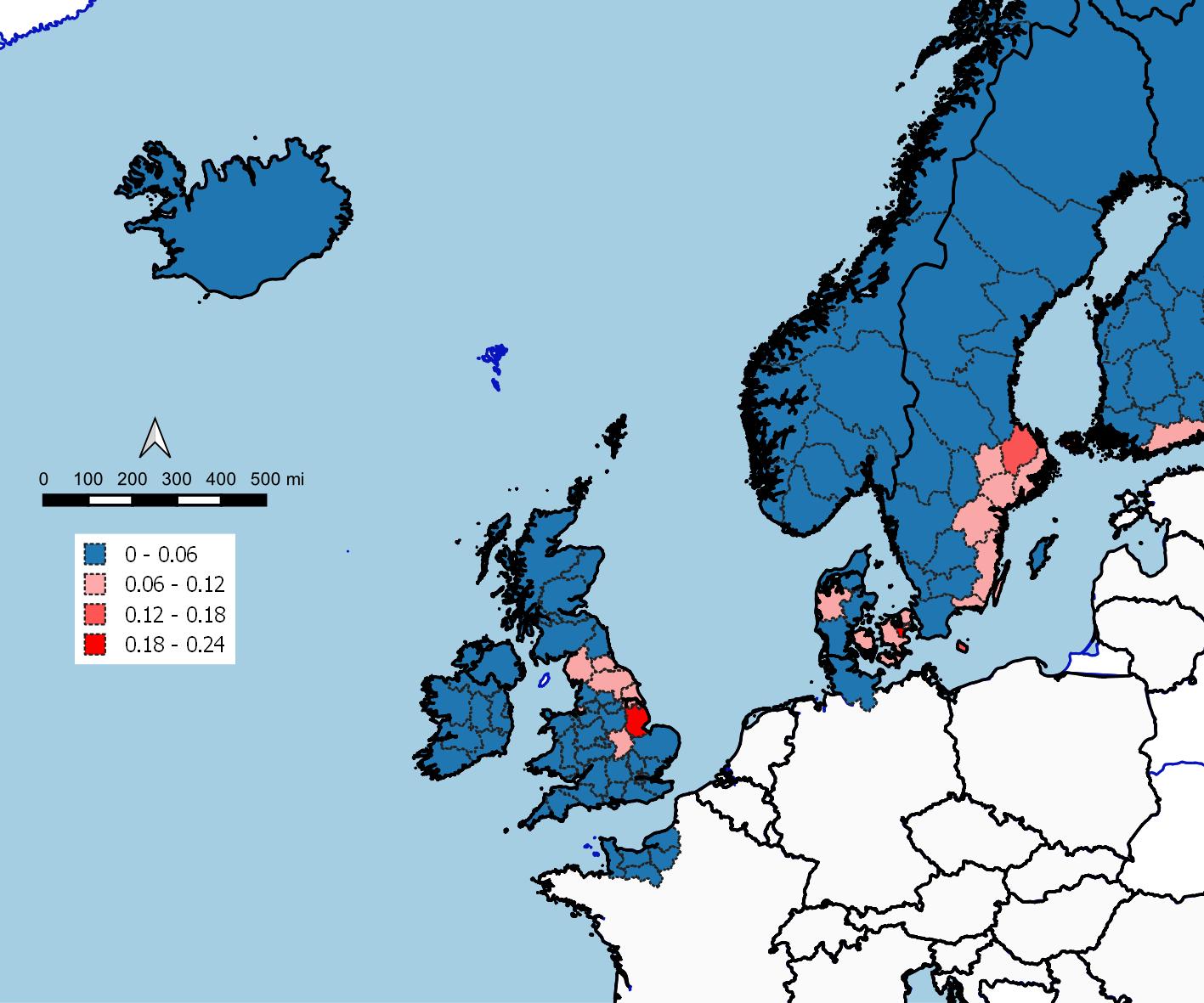

"Bee" place names account for 0.5% of all Norwegian place names. (This figure excludes words that contain the element "bygg" meaning "building"). It is most frequent in the south and west in regions close to the Swedish "bee" regions, specifically: Viken (2.3%), Oslo (1.6%) and Innlandet (0.9%). All remaining regions have less than 1%. The element "by" or "byn" occurs in 4.1% of Swedish place names. It is most common in the South, particularly in Upasala Laen with 18.4% of place names and Soederman Laen with 10.7%. The area includes the historic heartland of the Geats (Geats, 2021), home to the legendary hero Beowulf. The element "by" occurs in 6.4% of Danish place names. It is most common in areas close to Sweden, specifically in Østsjælland (essentially Copenhagen and its surroundings). This is the only place in all of northern Europe in which the proportion of "bee" place names (22.4%) exceeds that of Lincolnshire. "Bee" place names are relatively common in all areas of Denmark. Vejle Amt has the least; even here they comprise 4%. Figure 3 includes the previously disputed German region of Schleswig-Holstein at the southern end of the Jutland peninsula. To summarise, "bee" place names are not uniformly distributed throughout Scandinavia. Upasala Laen, Sweden and a small focus in Ostjaelland, Denmark are the only places where "bee" place names occur with frequencies similar to those found in Lincolnshire. They are least common in Norway. Judged by the distribution of "bee" place names in Scandinavia, the north east of Zealand in Denmark, and nearby areas of Sweden are most likely to have been the origin of the migrants who brought "bee" place names to England.

Figure 3 The proportion of "bee" place names in "Viking" homelands and major colonies.

There appear to be no "bee" names in Normandy (Calvados, Manche, Nord, Pas de Calais and Somme). The place name element that most closely resembles "bee" is "beuf", derived from búð, which translates to modern English as "booth" or "shed". According to Power (2012) there are very few Scandinavian place names of any sort in Ireland, "Considering the protracted domination of the Northmen, and considering the strong Danish element in the population of Waterford City and Gaultier, the number of Scandinavian names is surprisingly small: Waterford itself, Ballygunner, Ballytruckle, Helvic, Crooke and Faithlegg almost exhaust the list ..." There are no "bee" place names in Iceland according to a list available on the Internet (Meanings of Words used in Icelandic Place Names, undated). The string "by" does occur in 0.2% of place names, occasionally as part of the place name elements Byrg, Bygd or Byggd (meaning a rural district). The Norwegian equivalent of "by" was bær or bøur. In Iceland there are 114 such place names in total, ie 0.7% of the total. In Finland "Bee" place names account for 1.0%. They are locally common in the South, comprising 17% of all place names in Aland and 9% in Uusimaa (in which Hellsinki is located). I continue by looking for differences in the characteristics of the colonisations that might help explain the absence, or near absence, of "bee" place names in Normandy, Ireland and Iceland.

Scandinavian activity in Normandy is quite well documented, for example in the contemporary Annals of St-Bertin (Nelson, 1991). The story is complex. Internecine battles took place among both Scandinavians and Franks. Scandinavians sometimes fought on their own behalf against the Franks and sometimes fought as mercenaries in their pay. The following extract from the entry for 862 in the Annals of St-Bertin (Nelson, 1991, p99) is interesting. It illustrates the use of Scandinavian mercenaries in a dispute between Salomon (Duke of Normandy) and Robert (Count of Angers). "Salomon hired twelve Danish ships for an agreed fee, to use against Robert. These Robert captured on the River Loire and slew every man in the fleet, except for a few who fled into hiding. Robert now unable to put up with Salomon any longer, made an alliance against Salomon with the Northmen who had just left the Seine, before Salomon could ally with them against him. Hostages were exchanged and Robert paid them 6,000 lb of silver." The use of mercenaries also occurred in England. Their presence is implied in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for 897 (Giles, 1914) in which defeated combatants were left to pay for their own evacuation to Francia. DNA evidence from graves in Oxford and Dorset (see below) supports the existence of mercenaries operating in England. Cross in her PhD thesis (Cross, 2014) points to the similarity in the experience of France and England. Participants and victims experiencing these events were less likely to draw distinctions between England and Francia. Vikings operated in both theatres, travelling across the Channel according to the best opportunities. They attacked similar targets which they identified as centres of moveable wealth: trade emporia, towns and monasteries. Vikings in both regions also followed parallel tactics. As well as plundering, they imposed tribute or ‘Danegeld’ on the people of England and Francia. For these reasons, the inhabitants of England and Francia suffered broadly the same magnitude and nature of destruction." In 911 the Scandinavian presence was legitimised by the creation of the Duchy of Normandy (Rollo, 2020) which they controlled until 1204. Scandinavian involvement in Ireland (Downham, 2009) paralleled that in both England and Normandy, with early raids for booty followed by territorial conquests. Their main settlements were coastal. They were initially used as raiding bases, and later as trading centres. The dynasty of Ívar was a powerful force in Irish politics until the battle of Clontarf in 1014 and was a significant force in Dublin until the twelfth century. Its dominance was interrupted in 902 by a coalition of Irish forces, but resumed in 914. Iceland was a Scandinavian settlement by the end of the 9th century. Its occupation was complete by the end of the 10th century at the height of the Viking Age (Price, 2014). Iceland was primarily settled by Norwegians (History of Iceland, 2021). Finland was colonised by both Sweden and Russia in the 13th century. Colonisation took the form of religious crusades (Murray, 2017). Swedish influence persists to this day, with Swedish being one of the official languages.

Unfortunately, understanding the written history is complicated by changes both in the geography of political control, and the names used to describe peoples. The geo-political changes are illustrated by Ohthere (a guest of King Alfred) who described his voyages around Scandinavia. His report implies that areas in the south of present day Norway were Danish during the Viking age (Lund et al, 1984). The shifting names given to the various ethnic groups can be seen in a variety of sources. In England, Scandinavian invaders were referred to as either Danes or sometimes as "Northmen". Swanton (1996, p54 footnote) believes the terms to have been used interchangeably. Similarly in Normandy, the terms "Northmen" and "Danes" were sometimes used to describe the same people. For example, in Nelson’s (1991) translation of the Annals of St-Bertin, "Northmen" who were reported as "wreaking destruction" around Toulouse in the entry for 844, were described in the following year as, "... the Danes who had ravaged Acquitaine ...". In Ireland the historical records speak of both "Fair" and "Dark" foreigners. Downham (2009) rejects the idea that this was an ethnic distinction, but rather was a distinction between earlier and later groups.

By whatever names they were called, the forces that were active in England were also active in Normandy and Ireland. For example, the entry for 860 in the Annals of Saint Bertin (Nelson, 1991) tells us that, "The Danes on the Somme, ... sailed over to attack the Anglo-Saxons by whom, however, they were defeated and driven off." This is repeated in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle entry for the same year, "And in his (Ethelbert’s) days a large fleet came to land, and the crews stormed Winchester. And Osric the ealdorman, with the men of Hampshire, Ethelwulf the ealdorman, with the men of Berkshire, fought against the army, and put them to flight, and had possession of the place of carnage..." (Giles, 1914). In 893 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle again reports on the activities of continental Scandinavian forces in England (Giles, 1914). This time they came in support of the English Scandinavians who were engaged in an ongoing struggle with Wessex. "In this year the great army, about which we formerly spoke, came again from the eastern kingdom westward to Boulogne, and there was shipped; so that they came over in one passage, horses and all; and they came to land at Limne-mouth with two hundred and fifty ships. ... Then soon after that Hasten with eighty ships landed at the mouth of the Thames, and wrought himself a fortress at Milton; and the other army did the like at Appledore." The Scandinavians in Ireland were also involved in the invasion of England. The dynasty of Ivar that dominated Scandinavian Irish politics until 1014 (Downham, 2004) were also a part of the Great Heathen Army that conquered much of northern and eastern England. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle report for 867 (Giles, 1914) says that, "they gathered a large force, and sought the army at the town of York, and stormed the town, and some of them got within, and there was an excessive slaughter made of the North-humbrians, some within, some without, and the kings were both slain". The Annals of Ulster (undated web page) for 867 tell us who the attackers were, "The dark foreigners won a battle over the northern Saxons at York, in which fell Aelle, king of the northern Saxons." The identification of the Norsemen of Ireland with the invaders of Britain is repeated in the entry for 873, "Ímar, king of the Norsemen of all Ireland and Britain, ended his life".

My aim was to find out whether an international perspective would help explain the high prevalence of "bee" place names in parts of Scandinavian England. Among the Viking age colonies only Finland, a Swedish colony, had substantial numbers. Being a Swedish colony makes Finland a poor model for the Viking Age settlement of England. Iceland was also very different. It was a "settler" economy in the sense that the colonists occupied the land and worked it themselves. Ireland also differed from England, apparently lacking widespread Scandinavian settlement. The experience of Normandy was closest to that of England. Accordingly we might have expected similarities in their place names, however this was not the case. As we have seen, "bee" place names were not used in any other north west European Viking Age colony. A possible explanation would be that "bee" place names were already present in England. To examine this further, an obvious approach would have been to find out when "bee" place names first appeared. Unfortunately there is very little written evidence, possibly because of the destruction caused by the invaders themselves. There is a charter, purportedly dating from 675, relating to St. Peter’s Minster in Peterborough (Harley Roll Z 17, undated). It includes both "thorpe" and "bee" place names which would have supported a pre-Viking age origin for "bee" place names in England, however its provenance is disputed. Apparently religious institutions were not above forging documents to support their claims to property. In the absence of reliable place name sources, another alternative would be to look for DNA evidence.

DNA from the period is still scarce, but is gradually accumulating. There is evidence that mass settlement occurred on only one occasion after the Roman withdrawal. This comes from a study of the genetic structure of the British Population (Leslie et al, 2015). The research used a modern sample of 2039 people throughout the United Kingdom and a comparison group of 6,209 people from across Europe. The study found that the present population of the United Kingdom clustered into groups with various combinations of European DNA. To find out how many waves of immigrants had arrived since the Roman withdrawal they examined the length of strands of DNA in the individuals within their sample. It seems that DNA mixes somewhat like paint in a pot. Starting with two colours, paint would form strands when stirred. If we subsequently add a third colour and stir again, it would not be as well mixed as the first two. In this way we could see the sequence in which colours were added. In an analogous way, DNA mixes in strands or sequences of code. DNA from both parents is combined at conception, but it seems that some sequences can remain intact. The more frequently the population reproduces, the shorter those sequences become. Their length can be used as a guide to the number of generations after an "admixture event". A later addition to a mixed population should be identifiable by the longer DNA sequences associated with it. Assuming that the post Roman invaders mixed with the native Celtic population, that would have been a first "admixture event". If a significant Viking age immigration occurred subsequently and bred with the existing population, that would have been a second admixture. However, there was no evidence for this in mainland Britain. This led the authors to conclude, "… we see no clear genetic evidence of the Danish Viking occupation and control of a large part of England, either in separate UK clusters in that region or in the estimated ancestry profiles, suggesting a relatively limited input of DNA from the Danish Vikings ..."

Schiffels (2015) also published genetic research that year. They used a different technique, which focussed on the presence of relatively rare sequences of DNA. These were identified from a sample of modern Europeans. This enabled the researchers to construct a "tree" of European ancestry showing the occurrence of rare sequences within European lineages. They were also able to identify when those lineages diverged. The Dutch (taken as a proxy for Saxon) and Danish lineages separated more than 5,000 years ago. Ancient DNA samples from individuals buried at three sites in the east of England were compared with the European lineages. The sample size was small, consisting of only seven individuals with carbon 14 dates in the Anglo-Saxon period (the period that immediately predated the Viking age). Of three people in a group from Oakington, two had some Dutch ancestry and one had some Danish ancestry. Of three people in another group from Hinxton, a similar mix was found. The seventh person, also from Oakington, had a wider mix of ancestries including ancestry common to Finland, Cornwall, the Netherlands and Denmark.

A third study (Margaryan, 2020) examined ancient DNA in the North European Scandinavian world. The authors warn that we need to treat the findings with caution because of the scarcity of ancient DNA. Their methodology used DNA from the burial sites of 442 individuals. It was radiocarbon dated, with individuals classified as: Bronze Age, Iron Age, Early Viking Age, Late Iron age or Medieval/Early Modern. From this data set it was possible to examine the predecessors of Viking Age populations. With this information, together with other ancient DNA, they found that similarities existed in the DNA of Danish and English people before the Viking Age. Further analysis used a sample of modern European DNA. From this they identified typical components for Denmark, Sweden, Norway and a grouping of other "North Atlantic" areas. Using these typical components, the authors were able to say whether ancient samples contained "Danish-like", "Swedish-like", "Norwegian-like" or "North Atlantic-like" ancestry. This enabled them to conclude that, "... eastward movements (ie towards Finland and beyond – KB) mainly involved Swedish-like ancestry, whereas individuals with Norwegian-like ancestry travelled to Iceland, Greenland, Ireland and the Isle of Man. The first settlement in Iceland and Greenland also included individuals with North-Atlantic-like ancestry. A Danish-like ancestry is seen in present-day England, in accordance with historical records, place names, surnames and modern genetics, but Viking Age Danish-like ancestry in the British Isles cannot be distinguished from that of the Angles and Saxons, who migrated in the fifth to sixth centuries AD from Jutland and northern Germany." Among their sample were two Viking Age groups of adult males, one from Oxford and the other from Dorset. These may have been dead enemy combatants who had been thrown into burial pits. The groups probably contained mercenaries. The remains in Dorset predominantly comprised "British-like" DNA (35%) possibly from Scotland and/or Ireland, followed by "Norwegian-like" DNA (22%), "Danish-like" DNA (18%) and "Italian-like" DNA(16%). The remains in Oxford were also of mixed ancestry and comprised "Danish-like" DNA (52%), "Italian-like" DNA (17%), Swedish-like" DNA (14%), "British-like" DNA (8%) and "Norwegian-like" DNA (6%). The percentages were derived from the Supplementary Tables S6 (Margaryan, 2020). The same study reports that the DNA evidence from Ireland implies a Norwegian origin for the remains of three Viking Age individuals found in Dublin and one found in Connemara.

These three independent studies all point to the presence of people of Scandinavian descent in England before the Viking age. It would be interesting to know whether their language differed from that of their Saxon neighbours, if it did, that would increase the likelihood that they imported Scandinavian place names and language into England. The next section considers linguistic evidence

The science of linguistics allows us to understand the process by which languages change. When populations are separated their languages can evolve in different ways. If two "daughter" branches of a language have different characteristics we can assume that these arose after the languages diverged, on the other hand, common characteristics probably pre-date the divergence. Further separations can result in nested layers of change. Patrick Stiles (2013) provides a helpful review. The original Proto-Germanic language split into three branches: North, West and East Germanic. The latter was the language of the Goths and is now extinct. They migrated south and came into contact with Christian missionaries, who produced a Gothic version of the Bible for them in the fourth century (Hawkins, 2008). This is the earliest major extant Germanic text. West and North Germanic share some common characteristics not present in East Germanic implying that this was the first branch to separate. West Germanic then split from North Germanic. The split was gradual. West Germanic splitting at various times into English, Frisian, Dutch, Low German and High German, with some of the northern coastal areas of West Germanic continuing to share some characteristics present in North Germanic. Frisian is most closely related to modern English. However England was originally divided into Anglian and Saxon regions (see the section on "Tribal Boundaries"). Although the sequence of changes may be deduced from the study of existing languages the timescale cannot. For this, historical information of some sort is required. Dated reports of tribal migrations can be useful, as can reports that tribes spoke different languages. Perhaps best of all are datable phonetic written texts. There are a small number of datable texts from the Anglian regions of Mercia and Northumbria. Some of these show similarities with North Germanic, while comparable words in West Saxon follow Old Frisian/Old Saxon patterns. Stiles demonstrates this using third person genitive singular noun endings. He uses equivalents to the modern English word "father’s" to illustrate. The Old Norse equivalent is "fǫður" while the Mercian is "feadur" (ie the genitive singular endings are "ur"). This implies a North Germanic influence on Mercian. By comparison the Old Frisian equivalent is "feder" while the West Saxon is "fæder" (ie genitive singular endings are "er"). This implies a West Germanic influence on Saxon. Unfortunately written evidence from this period is extremely scarce, so these results must be treated with caution.

To understand the distribution of place names we need to think about which groups were involved in the process. By the Viking age English society had become deeply stratified, "Thus we can see how inextricably bound up lordship, judicial rights, military obligations, and the tenure of land were by the tenth century at the latest." (John, 1963). According to John, battles were fought by the thegns and their hlafords (lords) to whom they were responsible. Below this aristocracy were the churls or ceorls (perhaps visualised as peasant farmers). Following their victory, Scandinavian warriors would have replaced some of the local aristocracy. This elite might have named their large estates, however, they are unlikely to have concerned themselves with re-naming fields and small settlements. The section on DNA makes it clear that the Viking age conquest did not result in a mass immigration. From the point of view of the new land owners this would not necessarily have been a problem. The landed estates already had a compliant, productive, workforce. Although churls were free men, they were very much at the mercy of their landlords. They would have owned their ploughs and their oxen, but not the land. Accordingly they would have had little choice but to stay where they were and continue to work the fields that they had always worked. Not only did the peasants have the tools, they would also have had an organisational structure and a working knowledge of the fields. The churls would have new landlords when Scandinavian thegns replaced their English counterparts, but life could carry on as usual. The peasantry would continue to call their lands and fields by the names they had always used. This section is inevitably speculative.

I found the complete absence of "bee" place names in Normandy astonishing. Scandinavian activity there was so much part of an international project that it seemed most unlikely that, from the mix of Scandinavian people, none would choose a place name ending that was common in so much of Scandinavia. This made me wonder whether the conquest of Normandy was a purely military affair, and as a result, whether widespread naming or re-naming of settlements occurred at all. To test that hypothesis, I examined the frequency of other Scandinavian place names. Place name elements were listed in the web page "Norman Toponomy" (2019). The frequency of these was determined using place name data from the European Union data base "EuroStat". In total, Scandinavian names accounted for 7.3% of all place names, implying at least a modicum of Viking age settlement. The most common place name element is "tot", equivalent to the English "toft". It accounts for 2.0% of place names in Normandy. This compares with 0.5% in Lincolnshire. The absence or near absence of "bee" place names in Normandy, Ireland and Iceland, yet their presence in Finland, may imply that the name had gone out of use among the Danish and Norwegian groups in Western Europe, only remaining in favour with Swedish settlers in the East.

There is an isolated cluster of "bee" place names in coastal Cheshire and the south of Lancashire. Their existence has been attributed to the Scandinavian defeat in Dublin in 902 (Wainwright, 1975). He suggested that refugees fled to England where they were given sanctuary and where they established new settlements. Their arrival is recorded in "The Fragmentary Annals of Ireland" (Downham, 2009, p27). However, it seems unlikely that forces which colonised Ireland, where "bee" place names are absent, would start using them when they arrived in England. Furthermore, Downham points out that only small numbers from elite groups were likely to have left Dublin, and that in any event they returned to Ireland in 914. Wainwright’s Viking age explanation for "bee" place names in the west of Lancashire and Cheshire seems improbable.

DNA evidence supports the belief that both Saxon and Danish groups arrived in England at about the same time. It is possible that they settled in different areas. If they did, we might expect the distribution of place names to reflect this. Unfortunately, the geography of the settlement of Germanic tribes is not well documented. Only the Welsh monk Gildas (Gildas, 2012), writing in the early sixth century, left a (near) contemporary account. He tells us that he was born when the Britons had successfully fought back against a first Saxon offensive. The accuracy of his report has been questioned. Undoubtedly his description of the construction of Roman walls to defend the Britons from the Picts is inaccurate, however Hadrian’s wall was built some 400 years before Gildas. In general, the work appears to be a vehicle for religious invective rather than an unbiased history; however, unbiased histories are notoriously hard to find in any age. According to Gildas, after the withdrawal of the Romans, the Britons were repeatedly attacked by the Scots and the Picts. This is confirmed by Roman sources (Gibbon, 1974). In desperation they asked for help from the Saxons. The Saxons (presumably garrisoned as a buffer to the south of the Scots and Picts) then turned on their hosts. Inspired by their early success, Gildas reports that a second wave of barbarians arrived (he did not distinguish Angles and Jutes from Saxons). However, according to Gildas, the Britons fought back, regaining some of their earlier losses. Gildas reports that before this British resurgence, "... the fire of vengeance, justly kindled by former crimes (ie God’s revenge - KB), spread from sea to sea, fed by the hands of our foes in the east, and did not cease, until, destroying the neighbouring towns and lands, it reached the other side of the island, and dipped its red and savage tongue in the western ocean." From garrisons positioned to contain the Picts and Scots, we might suppose that the "fire of vengeance" dipped its red and savage tongue somewhere in the Solway Firth. To speculate, this might account for the occurrence of "bee" place names in Westmorland and Cumberland, while the British resurgence might account for the differences in the frequency of "bee" names between Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Two hundred or so years after these events, the Venerable Bede (Bede, 1999) tried to piece together the pattern of settlement. He believed that the Jutes settled Kent while the Angles and Saxons settled other parts of England as follows: "From the Angles are descended ... East-Angles, the Midland-Angles, the Mercians, all the race of the Northumbrians, that is, of those nations that dwell on the north side of the river Humber, and the other nations of the Angles". There is some overlap between Bede’s account of places settled by the Angles and places settled by the Viking age Scandinavians some four centuries later. This makes it difficult to disentangle their separate effects. Bede would have been unable to reconstruct the sequence and the extent of tribal boundaries in the immediate post Roman period with any certainty. Moreover, he had a religious preference for giving his native region of Bernicia an Anglian heritage, with its "angelic" connotations (Richter, 1984). If Bernicia, lying to the north of the Tees, had been a Saxon Kingdom, he might have preferred not to advertise the fact. However, a Saxon origin for Bernicia may be implied in the Scottish term "Sassenach" to describe their southern neighbours. This is deeply speculative, however, it is a period for which speculation is the norm. Much of Lancashire and Elmet in Yorkshire remained Celtic until well after the initial phase of post Roman Germanic conquest. Blair (1977 pp 48-49) cites near contemporary reports by Wilfred implying that extensive English colonisation of land to the West of the Pennines did not take place until after 650. Perhaps the first phase of Scandinavian colonisation, described earlier by Gildas, stalled after bursting across the headwaters of the River Tees into Cumbria and Westmorland. This would correspond with the severing of the Celtic lands of the Old North. (Or perhaps Gildas, although speaking shortly after the events, lacked the benefits of modern scholarship.) To the south of Deira (comprising much of modern Yorkshire) lay the Kingdom of Lindsey (approximately modern Lincolnshire), in which the highest concentration of "bee" place names lies. Over the Wash and to the south of Lindsey lay the separate Kingdom of East Anglia, a place where "bee" place names are rare (except for some coastal areas). I speculate that East Anglia, like Bernicia, was colonised by Saxons in the first wave of post Roman invasions and only subsequently became Anglian.

I have tried to highlight where my findings are most dubious. Inevitably some speculation is necessary. However, some of the evidence presented strongly implies an early date for the Scandinavian influence on English language and place names. The lack of "bee" place names in other north-west European countries is difficult to explain in any other way, when the contemporary historical evidence strongly suggests that England, Normandy and Ireland were invaded by the same peoples. I have reported on three studies of DNA. All three provide evidence of Danish ancestry in England before the Viking Age invasion. Two find no evidence of a mass Viking Age immigration. It seems perverse to suppose that Viking Age forces in the north-west of Europe, who did not leave "bee" place names anywhere else, left them in great swathes of England, while simultaneously supposing that a mass migration in the immediate post Roman period, which included Scandinavian Angles and Jutes, left no Scandinavian place names. "Bee" place names are absent from much of Viking Age Scandinavian territory in England, not because of erratic place name choices made during the Viking age, but because it was the Angles and Jutes, in the post Roman period, who were responsible for leaving them.

Comments and corrections to kenbuckingham@yahoo.co.uk

The Annals of Ulster. (undated web page). Retrieved from https://celt.ucc.ie//published/T100001A/index.html.

Bede, Colgrave B, McClure J, Collins R. 1999. The ecclesiastical history of the English people. Cuthbert's letter on the death of Bede ; The greater chronicle ;

Bede's letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press.

Blair PH. 1977. An introduction to Anglo-Saxon England. Cambridge University Press.

Buckingham, J.K. 2020. The origin of Danish settlement in England. Wiðowinde, 194, 24-29.

Cross, KC. 2014. Enemy and ancestor: viking identities and ethnic boundaries in England and Normandy, c.950-c.1015. Doctoral thesis, UCL (University College London).

Downham, C. 2004. The historical importance of Viking-Age Waterford. University of Aberdeen

Downham C. 2009. Viking kings of Britain and Ireland: the dynasty of Ívarr to A.D. 1014. Dunedin.

Elmet. 2021 Jan 8. Wikipedia

Geats. 2021 Feb 5. Wikipedia.

Gibbon E, Bury JB. 1974. The history of the decline and fall of the Roman Empire edited in seven volumes. Methuen.

Gildas. 2012. The Project Gutenberg EBook (#1949) of On the Ruin of Britain.

Giles JA. 1914. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle edited from the translation in Monumenta Historica Britannica and other versions, by the late J.A. Giles, D.C.L. G. Bell and Sons, Ltd.

Guthrum. undated. Retrieved from https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/source/guthrum.asp

Harley Roll Z 17. Digitised Manuscripts

Hawkins J A. 2008. The World’s Major Languages. Routledge. Accessed on: 10 Mar 2021. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.4324/9780203301524.ch2.

History of Iceland. 2021. Wikipedia

John E. 1963. English feudalism and the structure of Anglo-Saxon society. Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 46:14–41.

Leslie, S., Winney, B., Hellenthal, G. et al. 2015. The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature 519, 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14230

Lund N, Fell CE, Crumlin-Pedersen O, Sawyer PH. 1984. Two voyagers at the court of king Alfred: the ventures of Ohthere and Wulfstan, together with the Description of northenEurope from the old English Orosius. Sessions.

Margaryan, A., Lawson, D.J., Sikora, M. et al. 2020 Population genomics of the Viking world. Nature 585, 390–396.

Meanings of Words used in Icelandic Place Names. undated. Icelandic Roots. Retrieved from http://www.icelandicroots.com/icelandic-places-and-meanings.

Murray, A. V. 2017. Crusade and conversion on the Baltic frontier, 1150-1500. Routledge.

Nelson JL. 1991. The Annals of St-Bertin: ninth-century histories. Manchester University Press.

Norman toponymy. 2019 Sep 14. Wikipedia.

Power P. 2012. Place-names of decies. Hardpress Publishing.

Price TD, Gestsdóttir H. 2014. The Peopling of the North Atlantic: Isotopic Results from Iceland. Journal of the North Atlantic 2014:146

Richter M. 1984. Bede’s Angli: Angles or English? Peritia 3:99–114.

Rollo. 2020 Nov 10. Wikipedia.

Schiffels S, Haak W, Paajanen P, Llamas B, Popescu E, Loe L, Clarke R, Lyons A, Mortimer R, Sayer D, et al. 2016. Iron Age and Anglo-Saxon genomes from East England reveal British migration history. Nature Communications 7.

Stiles PV. 2013. The Pan-West Germanic Isoglosses and the Subrelationships of West Germanic to Other Branches. Unity and Diversity in West Germanic, I NOWELE / North-Western European Language Evolution NOWELE. North-Western European Language Evolution NOWELE 66:5–38.

Swanton MJ. 1996. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle. J. M. Dent.

Wainwright FT, Finberg HPR. 1975. Scandinavian England.

Mapping software was downloaded from https://qgis.org/en/site/

Boundary and place name data were downloaded from the European Commission’s Eurostat at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/gisco/geodata/reference-data/administrative-units-statistical-units/nuts

1 For comparability across Scandinavian Europe I used the geographical regions defined by the European Union’s Nomenclature of Territorial Units. In countries with relatively low population densities, Level 3 Territorial Units provide suitably sized geographies, however for the UK, Level 3 is too detailed. Accordingly I use Level 2 in England. This gives areas of similar geographical size to the rest of Scandinavian Europe. Note however, that the Tees Valley region straddles the River Tees, including places in South Teesside, North Teesside and Durham. This masks the important distinction in densities to the North and South of the Tees. Figure 2 provides greater detail.

2 The proportional density for Schleswig-Holstein is included below Denmark. While "bee" names are present, their density is relatively low. Historically parts of it have been Danish.